Data Challenge Lab Home

Model evaluation [model]

(Builds on: Models with multiple variables)

library(tidyverse)

library(modelr)

A crucial part of the modeling process is determining the quality of your model. In this reading, we’ll explore how to compare different models to each other and pick the one that best approximates your data.

The problem

In order to illustrate the process of model evaluation, we’re going to use simulated data. To simulate data, you pick a function and use that function to generate a series of data points. We can then compare any models we make to the true function used to generate the data.

Note that you almost always won’t actually know the functional representation underlying your data. If you did, you probably wouldn’t need a model in the first place.

For our simulated data, let’s assume there’s some phenomenon that has a functional representation of the form

y = f(x)

In other words, the phenomenon is purely a function of the variable x,

and so, if you know x, you can figure out the behavior of the

phenomenon. Here’s the function f() that we’ll use.

# True function

f <- function(x) x + 50 * sin((pi / 50) * x)

f() is the true function, but let’s also assume that any measurements

of y will have errors. To simulate errors, we need a function that

adds random noise to f(). We’ll call this function g().

# Function with measurement error

g <- function(x) f(x) + rnorm(n = length(x), mean = 0, sd = 20)

We can use g() to generate a random sample of data.

# Function that generates a random sample of data points, using g()

sim_data <- function(from, to, by) {

tibble(

x = seq(from = from, to = to, by = by),

y = g(x)

)

}

# Generate random sample of points to approximate

set.seed(439)

data_1 <- sim_data(0, 100, 0.5)

Here’s a plot of both the simulated data (data_1), and the true

function. Our job is now to use the simulated data to create a function

that closely approximates the true function.

tibble(x = seq(0, 100, 0.5), y = f(x)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x, y)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point(data = data_1) +

labs(title = "True function and simulated data")

The loess() model

Given the shape of our data, the stats::loess() function is a good

place to start. loess() works by creating a local model at each data

point. Each of these local models only uses data within a given distance

from that point. The span parameter controls how many points are

included in each of these local models. The smaller the span, the fewer

the number of points included in each local model.

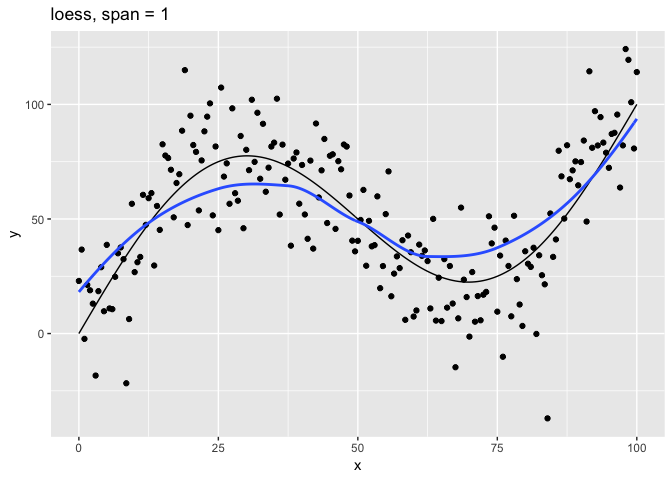

To better understand the effect of the span parameter, let’s plot

loess() models with different values of span.

The function plot_loess() fits a model using loess(), then plots the

model predictions and the underlying data.

# Plot loess model for given span

plot_loess <- function(span) {

data_1 %>%

mutate(f = f(x)) %>%

add_predictions(loess(y ~ x, data = data_1, span = span)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x)) +

geom_line(aes(y = f)) +

geom_point(aes(y = y)) +

geom_line(aes(y = pred), color = "#3366FF", size = 1) +

labs(

title = str_glue("loess, span = {span}"),

y = "y"

)

}

Now, we can use purrr to apply plot_loess() to a vector of different

span values.

c(10, 1, 0.75, 0.1, 0.01) %>%

map(plot_loess) %>%

walk(print)

The span parameter clearly makes a big difference in the model:

span = 10smooths too much and washes out the variability in the model.span = 1is much better, but still has a bit too much smoothing.span = 0.75is the default and does a reasonably good job.span = 0.1has too little smoothing. The added complexity has started tracking the random variation in our data.span = 0.01went way too far and started to fit individual random points.

It’s clear that the model with span = 0.75 comes closest to following

the form of the true model. The models with span equal to 0.1 and

0.01 have overfit the data, and so won’t generalize well to new

data.

Test and training errors

Let’s return to the question of how to measure the quality of a model.

Above, we could easily visualize our different models because they each

had only one predictor variable, x. It will be much harder to

visualize models with many predictor variables, and so we need a more

general way of determining model quality and comparing models to each

other.

One way to measure model quality involves comparing the model’s predicted values to the actual values in data. Ideally, we want to know the difference between predicted and actual values on new data. This difference is called the test error.

Unfortunately, you usually won’t have new data. All you’ll have is the data used to create the model. The difference between the predicted and actual values on the data used to train the model is called the training error.

Since the expected value for the error term of g() is 0 for each

x, the best possible model for new data would be f() itself. The

error on f() itself is called the Bayes error.

Usually, you won’t know the true function f(), and you won’t have

access to new test data. In our case, we simulated data, so we know

f() and can generate new data. The following code creates 50 different

samples, each the same size. We’ll use these 50 different samples to get

an accurate estimate of our test error.

set.seed(886)

data_50 <-

1:50 %>%

map_dfr(~ sim_data(0, 100, 0.5))

Now, we need a way to measure the difference between a vector of predictions and vector of actual values. Two common metrics include:

- Root-mean-square error (RMSE):

sqrt(mean((y - pred)^2, na.rm = TRUE)) - Mean absolute error (MAE):

mean(abs(y - pred), na.rm = TRUE)

Both measures are supported by modelr. We’ll use RMSE below.

Now, we’ll train a series of models on our original dataset, data_1,

using a range of span’s. Then, for each model, we’ll calculate the

training error on data_1 and the test error on the new data in

data_50.

First, we need to create a vector of different span values.

spans <- 2^seq(1, -2, -0.2)

Next, we can use purrr to iterate over the span values, fit a model for each one, and calculate the RMSE.

errors <-

tibble(span = spans) %>%

mutate(

train_error =

map_dbl(span, ~ rmse(loess(y ~ x, data = data_1, span = .), data_1)),

test_error =

map_dbl(span, ~ rmse(loess(y ~ x, data = data_1, span = .), data_50))

)

The result is a tibble with a training error and test error for each

span.

errors

## # A tibble: 16 x 3

## span train_error test_error

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 2 27.7 27.4

## 2 1.74 26.9 26.7

## 3 1.52 25.9 25.7

## 4 1.32 24.6 24.6

## 5 1.15 22.8 23.0

## 6 1 21.3 21.8

## 7 0.871 19.3 20.4

## 8 0.758 18.7 20.2

## 9 0.660 18.5 20.2

## 10 0.574 18.4 20.3

## 11 0.5 18.4 20.3

## 12 0.435 18.3 20.4

## 13 0.379 18.1 20.4

## 14 0.330 17.8 20.4

## 15 0.287 17.4 20.6

## 16 0.25 17.2 20.8

It would be useful to compare these errors to the Bayes error, the error

on the true function, which you can think of as the “best-case-scenario”

error. The RMSE Bayes error is 20, the standard deviation of the random

errors added by g(). We can check this with an approximation using

data_50.

bayes_error <- 20

data_50 %>%

summarize(bayes_error = sqrt(mean((y - f(x))^2, na.rm = TRUE))) %>%

pull(bayes_error)

## [1] 19.9741

Now, let’s plot the training, test, and Bayes errors by span.

bayes <- tibble(

span = range(errors$span),

type = "bayes_error",

error = bayes_error

)

errors %>%

gather(key = type, value = error, -span) %>%

ggplot(aes(1 / span, error, color = type)) +

geom_line(data = bayes) +

geom_line() +

geom_point() +

labs(

title = "Errors as a function of increasing model complexity",

color = NULL

)

Mapping 1 / span to the x-axis makes the plot easier to interpret

because smaller values of span create more complex models. The

leftmost points indicate the simplest models, and the rightmost indicate

the most complex.

The lowest test error is around 20.18, and came from the model with

span ≈ 0.758. Note that the default value of span in loess() is

0.75, so the default here would have done pretty well.

You can see that as the model increases in complexity, the training

error (blue line) continually declines, but the test error (green line)

actually starts to increase. The test error increases for values of

span that make the model too complex overfit the training data.

We used data_50, our new data, to calculate the actual test error. As

we’ve said, though, you usually won’t have access to new data and so

won’t be able to calculate the test error. You’ll need a way to

estimate the test error using the training data. As our plot indicates,

however, the training error is a poor estimate of the actual test error.

In the next section, we’ll discuss a better way, called

cross-validation, to estimate the test error from the training data.

Cross-validation

There are two key ideas of cross-validation. First, in the absence of new data, we can hold out of a random portion of our original data (the test set), train the model on the rest of the data (the training set), and then test the model on test set. Second, we can generate multiple train-test pairs to create a more robust estimate of the true test error.

modelr provides two functions for generating these train-test pairs:

crossv_mc() and crossv_kfold(). We’ll introduce these functions in

the next section.

Generating train-test pairs with crossv_mc() and crossv_kfold()

crossv_mc() and crossv_kfold() both take your original data as input

and produce a tibble that looks like this:

data_1 %>%

crossv_kfold()

## # A tibble: 5 x 3

## train test .id

## <list> <list> <chr>

## 1 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 1

## 2 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 2

## 3 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 3

## 4 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 4

## 5 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 5

Each row represents one train-test pair. Eventually, we’re going to build a model on each train portion, and then test that model on each test portion.

crossv_mc() and crossv_kfold() differ in how they generate the

train-test pairs.

crossv_mc() takes two parameters: n and test. n specifies how

many train-test pairs to generate. test specifies the portion of the

data to hold out each time. Importantly, crossv_mc() pulls randomly

from the entire dataset to create each train-test split. This means that

the test sets are not mutually exclusive. A single point can be present

in multiple test sets.

crossv_kfold() takes one parameter: k, and splits the data into k

exclusive partitions, or folds. It then uses each of these k folds

as a test set, with the remaining k - 1 folds as the training set. The

main difference between crossv_mc() and crossv_kfold() is that the

crossv_kfold() test sets are mutually exclusive.

Now, let’s take a closer look at how these functions works. The

following code uses crossv_kfold() to create 10 train-test pairs.

set.seed(122)

df <-

data_1 %>%

crossv_kfold(k = 10)

df

## # A tibble: 10 x 3

## train test .id

## <list> <list> <chr>

## 1 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 01

## 2 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 02

## 3 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 03

## 4 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 04

## 5 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 05

## 6 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 06

## 7 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 07

## 8 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 08

## 9 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 09

## 10 <S3: resample> <S3: resample> 10

The result is a tibble with two list-columns: train and test. Each

element of train and test is a resample object, which you might not

have seen before. Let’s look at the first row, the first train-test

pair.

train_01 <- df$train[[1]]

train_01

## <resample [180 x 2]> 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, ...

test_01 <- df$test[[1]]

test_01

## <resample [21 x 2]> 2, 8, 21, 43, 53, 63, 78, 81, 85, 101, ...

Each resample object is actually a two-element list.

glimpse(train_01)

## List of 2

## $ data:Classes 'tbl_df', 'tbl' and 'data.frame': 201 obs. of 2 variables:

## ..$ x: num [1:201] 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4.5 ...

## ..$ y: num [1:201] 22.95 36.64 -2.32 21.26 18.88 ...

## $ idx : int [1:180] 1 3 4 5 6 7 9 10 11 12 ...

## - attr(*, "class")= chr "resample"

The first element, data is the original dataset. The second element,

idx, is a set of indices that indicate the subset of the original data

to use.

We can use a set operation to verify that the train and test sets are mutually exclusive. In other words, there is no point in a given train set that is also in its corresponding test set, and vice versa.

is_empty(intersect(train_01$idx, test_01$idx))

## [1] TRUE

The union of each train and test set is just the complete original dataset. We can verify this by checking that the set of all train and test indices contains every possible index in the original dataset.

setequal(union(train_01$idx, test_01$idx), 1:201)

## [1] TRUE

resample objects are not tibbles. Some model functions, like lm(), can

take resample objects as input, but loess() cannot. In order to use

loess(), we’ll need to turn the resample objects into tibbles.

as_tibble(test_01)

## # A tibble: 21 x 2

## x y

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.5 36.6

## 2 3.5 18.5

## 3 10 26.8

## 4 21 79.3

## 5 26 68.5

## 6 31 102.

## 7 38.5 76.4

## 8 40 73.6

## 9 42 37.1

## 10 50 40.5

## # … with 11 more rows

Resample objects waste a lot of space, since each one contains the full dataset. A new package rsample is being developed to support tidy modeling in a more space-efficient way.

Process

crossv_kfold() and crossv_mc() just generate train-test pairs. In

order to carry out cross-validation, you still need to fit your model on

each train set and then evaluate it on each corresponding test set. In

this section, we’ll walk you through the process.

1 Create a function to calculate your test error

First, you’ll need a function that calculates the test error using some metric. We’ll use RMSE. The following function returns the RMSE for a given span, train set, and test set.

rmse_error <- function(span, train, test) {

rmse(loess(y ~ x, data = as_tibble(train), span = span), as_tibble(test))

}

2 Create a function to calculate CV error

Next, you need a function that iterates over all your train-test pairs, calculates the test error for each pair, and then calculates the mean of the errors and the standard error of the mean.

span_error <- function(span, data_cv) {

errors <-

data_cv %>%

select(-.id) %>%

add_column(span = span) %>%

pmap_dbl(rmse_error)

tibble(

span = span,

error_mean = mean(errors, na.rm = TRUE),

error_se = sd(errors, na.rm = TRUE) / sqrt(length(errors))

)

}

3 Create your train-test pairs

Use either crossv_mc() or crossv_kfold() to generate your train-test

pairs. We’ll use crossv_mc() to generate 10 train-test pairs with test

sets consisting of approximately 20% of the data.

set.seed(430)

data_mc <- crossv_mc(data_1, n = 10, test = 0.2)

4 Calculate the CV error for different values of your tuning parameter

We want to compare different values of span, so we also need to

iterate over a vector of different span values. We’ll calculate the CV

error for all spans using these train-test pairs.

errors_mc <-

spans %>%

map_dfr(span_error, data_cv = data_mc)

errors_mc %>%

knitr::kable()

| span | error_mean | error_se |

|---|---|---|

| 2.0000000 | 28.77162 | 0.4598847 |

| 1.7411011 | 27.90898 | 0.4590082 |

| 1.5157166 | 26.80809 | 0.4633976 |

| 1.3195079 | 25.42115 | 0.4763469 |

| 1.1486984 | 23.47827 | 0.5162414 |

| 1.0000000 | 21.89512 | 0.5574787 |

| 0.8705506 | 19.70633 | 0.6247474 |

| 0.7578583 | 19.00509 | 0.6083815 |

| 0.6597540 | 18.79978 | 0.5899732 |

| 0.5743492 | 18.80655 | 0.5736369 |

| 0.5000000 | 18.82917 | 0.5663217 |

| 0.4352753 | 18.87305 | 0.5575942 |

| 0.3789291 | 18.85135 | 0.5313073 |

| 0.3298770 | 18.78642 | 0.4918808 |

| 0.2871746 | 18.72327 | 0.5003602 |

| 0.2500000 | 18.70617 | 0.5152749 |

5 Choose the best model

Now, we need to compare the different models and choose the best value

of span.

Because we simulated our data, we can compare the CV estimates of the test error with the actual test error.

errors_mc %>%

left_join(errors, by = "span") %>%

ggplot(aes(1 / span)) +

geom_line(aes(y = test_error, color = "test_error")) +

geom_point(aes(y = test_error, color = "test_error")) +

geom_line(aes(y = error_mean, color = "mc_error")) +

geom_pointrange(

aes(

y = error_mean,

ymin = error_mean - error_se,

ymax = error_mean + error_se,

color = "mc_error"

)

) +

labs(

title = "Cross-validation and test errors",

y = "error",

color = NULL

)

From this plot, we can see that CV error estimates from crossv_mc()

underestimate the true test error in the range with 1/span > 1. The

line ranges reflect one standard error on either side of the mean error.

Usually, you won’t have access to the true test error, so we need a way

to choose the best value of span using just the CV errors. Here’s the

rule-of-thumb for choosing a tuning parameter when you only know the CV

errors.

- Start with the parameter that has the lowest mean CV error. In this

case, that would be

span= 0.25 (on the plot,1/span= 4) with an mean CV error of approximately 18.7. - Then choose the simplest model whose mean CV error is within one

standard error of the lowest value. The standard error for

span= 0.25 is approximately 0.5, so we are seeking the simplest model with a mean CV error less than 19.2. This occurs forspan≈ 0.758 (on the plot,1/span≈ 1.32).

We saw above that if we knew the test error, we would choose span ≈

0.758 as the optimal parameter. The one-standard-error rule of thumb

would lead us to choose the same optimal parameter without having to

know the test error. The test error for this span is very close to the

Bayes error of 20.

errors %>%

top_n(-1, test_error) %>%

select(span, test_error) %>%

knitr::kable()

| span | test_error |

|---|---|

| 0.7578583 | 20.1787 |